Smartphones and chatbots have changed how we search for knowledge. Information is always within reach, and we can learn in any order we choose. This feels new. But have we been here before, along the history? SU’s historian of ideas Linn Holmberg shows that Europe has experienced a similar transformation before.

In the eighteenth century, dictionaries gave readers a new kind of freedom. They were more than books. They were a form of early information technology that revolutionised how people accessed and consumed knowledge. Instead of reading long texts from beginning to end, readers could look up detached pieces of information quickly, jumping between topics as they pleased.

This way of learning became extremely popular. So popular, in fact, that people began to describe it as an epidemic. Journals spoke of a “Dictionary craze”. Across Europe, dictionaries exploded in number. They appeared not only in traditional subjects like geography, chemistry, theology, medicine and law, but also in unexpected areas: fishing, fashion, even love.

Linn Holmberg, Historian of Ideas, Department of Culture and Aesthetics, Stockholm University, has studied how people reacted to this new genre. She analysed sixteen literary journals published in France, England, Germany, the Dutch Republic and Sweden over a period of 124 years. What she found surprised her.

Dictionaries provoked strong emotions. Opinions were sharply divided. Some welcomed them as tools of enlightenment. Others feared what they might do to knowledge itself. One journal complained: “One can now expect almost nothing but dictionaries”.

Many critics worried that dictionaries encouraged a shallow understanding of the world. They warned that readers would stop thinking deeply, relying instead on simplified summaries. They also argued that many dictionaries were poorly made, full of errors, compiled by writers who lacked expertise. In certain fields, such as medicine and law, this was seen as especially dangerous.

The debate was not only about books. It was about trust, truth and the future of learning. Over time, the panic faded. With the rise of the research university and the professionalisation of the sciences, new systems for verifying facts emerged.

Experts and academic institutions gradually took over the task of compiling large-scale dictionaries. Slowly, dictionaries became what we know them as today: monuments of authoritative knowledge.

New technologies always spark both enthusiasm and worry

Holmberg’s research offers a striking parallel to our own era. Then, as now, new technologies sparked both enthusiasm and worry. They raised concerns about whether the road to knowledge could be shortened without losing something vital along the way.

The eighteenth-century dictionary craze reminds us that information revolutions are never only about access. They are also about how we think, what we trust, and what kind of knowledge we want to build.

Enjoy also the original story, in Swedish.

Related news

-

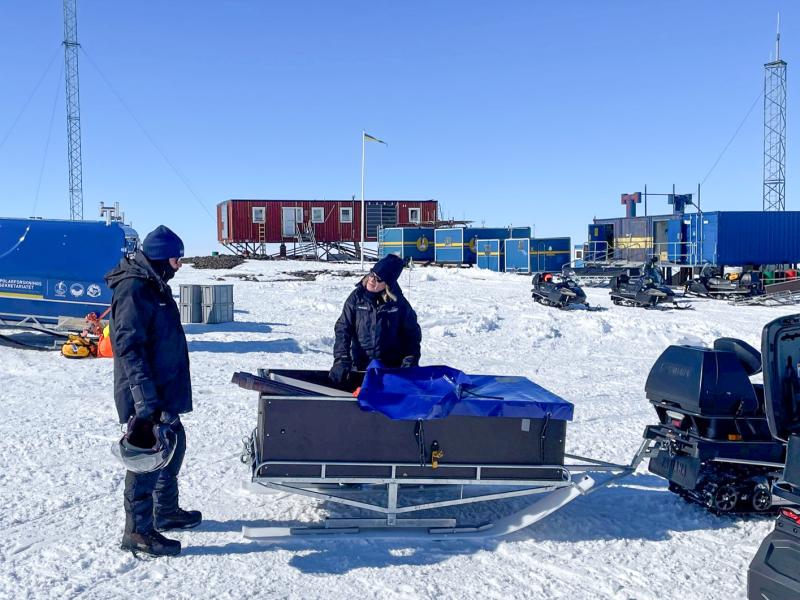

Antarctic expedition searches for clues to future sea-level rise

CIVIS Highlights

8 januari 2026 -

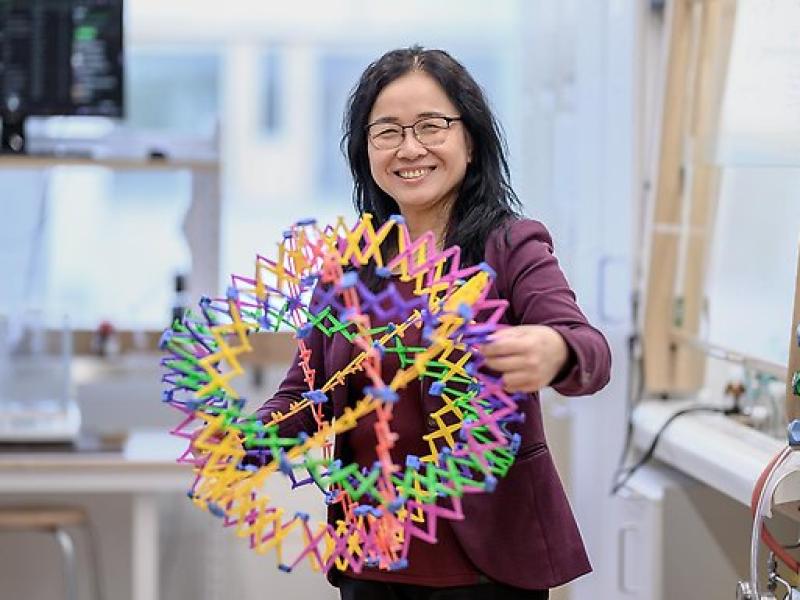

Cutting-edge research at Stockholm University on MOFs, Nobel Prize-Winning Materials

CIVIS Highlights

11 december 2025 -

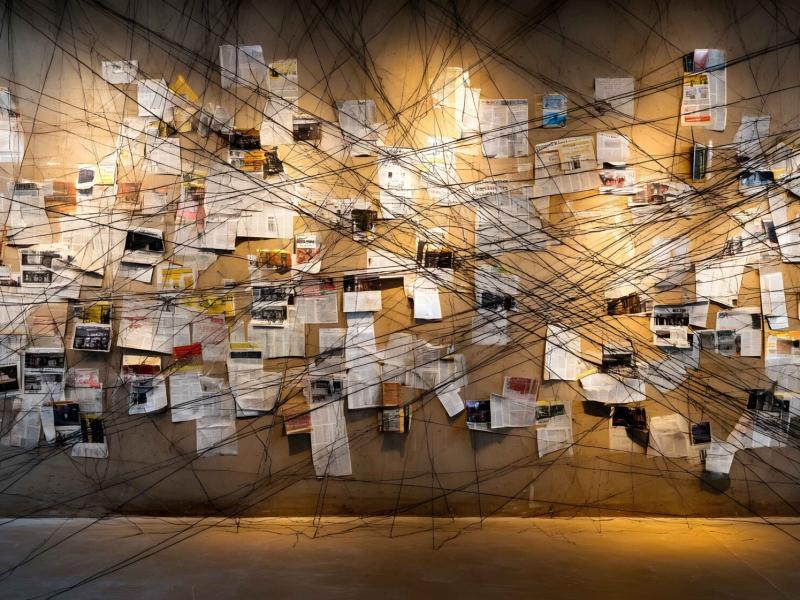

Populism and Conspiracy - a European Study by the University of Salzburg

CIVIS Highlights

6 november 2025