Conventional circuit boards are made from materials that are difficult or costly to recycle at the end of their lifecycle, and they often end up in landfill, where they can release harmful chemicals into the surrounding land. In 2024, 62 million tonnes of electronic waste were discarded, with less than 17% recycled in the EU.

In a paper titled ‘Additively manufacturing printed circuit boards with low waste footprint by transferring electroplated zinc tracks’ and published in the journal Communications Materials, the team show how they set out to help tackle to problem by developing what they call a ‘growth and transfer additive manufacturing process’, which generates conductive metal tracks on biodegradable surfaces.

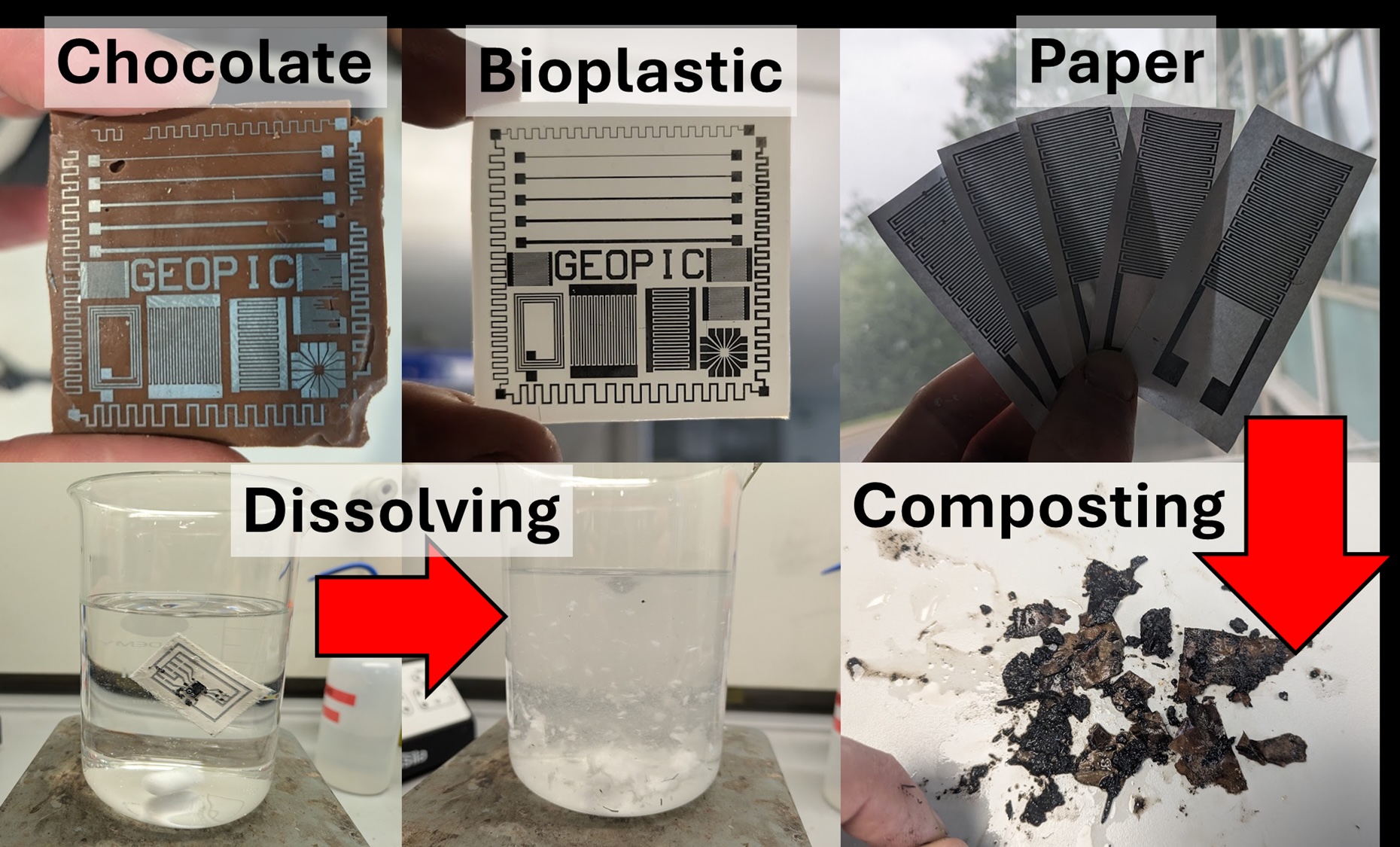

Once the circuits are no longer needed, 99% of their materials can be disposed of safely through ordinary soil composting or by dissolving in widely available chemicals like vinegar. The research aims to address the growing problem of electronic waste, or e-waste, caused by the materials used in the construction of modern electronic devices.

How does it work?

Unlike conventional circuit boards, which use copper to conduct electricity, the team use zinc instead to create metal traces just five microns wide. The process works by electroplating conductive bulk zinc onto a temporary carrier, which is then transferred to a biodegradable base.

The resulting circuits perform comparably to traditional boards, and the paper shows how the team have tested them successfully in multiple devices, including tactile sensors, LED counters, and temperature sensors. The team have also shown that the materials’ performance remains stable after more than a year kept in ambient conditions.

A life cycle assessment conducted by the team compared the potential environmental impact of their new PCBs against conventional boards. Their findings show that the biodegradable PCBs could enable a 79% reduction in global warming potential, and a 90% reduction in resource depletion, suggesting that they could enable significant reductions in the environmental impact of electronic devices.

The work demonstrates a major step toward circular electronics, where devices are designed from the outset for reuse, recycling, or safe degradation. Discarded devices already generate tens of millions of tonnes of waste annually, so our research could have far-reaching impacts for consumer electronics, internet-of-things devices and disposable sensors in the future”, says Dr Jonathon Harwell, of the University of Glasgow’s James Watt School of Engineering, and the paper’s first author.

Professor Jeff Kettle, the paper’s corresponding author, emphasises that “one key aspect of our work is that almost any substrate material can be used in the process, ranging from paper and bioplastics for more realistic applications, to chocolate for tasty but probably not very practical demonstrations. We are now exploring ways to adapt this technique to other fields such as mouldable electronics or biosensing, which could also benefit from a cheap and versatile way to make high quality circuits with low environmental footprints.”

Searching for new ways to make industries more sustainable

The research is part of a broader activity at the University of Glasgow-led Responsible Electronics and Circular Technology Centre (REACT). Backed by more than £6m from UKRI, the Centre is one of five Green Economy Centres which are seeking to find new ways to make industries more sustainable.

The Centre’s researchers are investigating complementary technologies such as scalable waste electrical and electronic equipment processing and recycling.

Latest Highlights:

Major study involving the University of Bucharest rewrites the history of European dinosaurs

Pathogen hijacks fruit ripening program in citrus plants

Antarctic expedition searches for clues to future sea-level rise

Scientists track adaptation of bird flu in dairy cattle