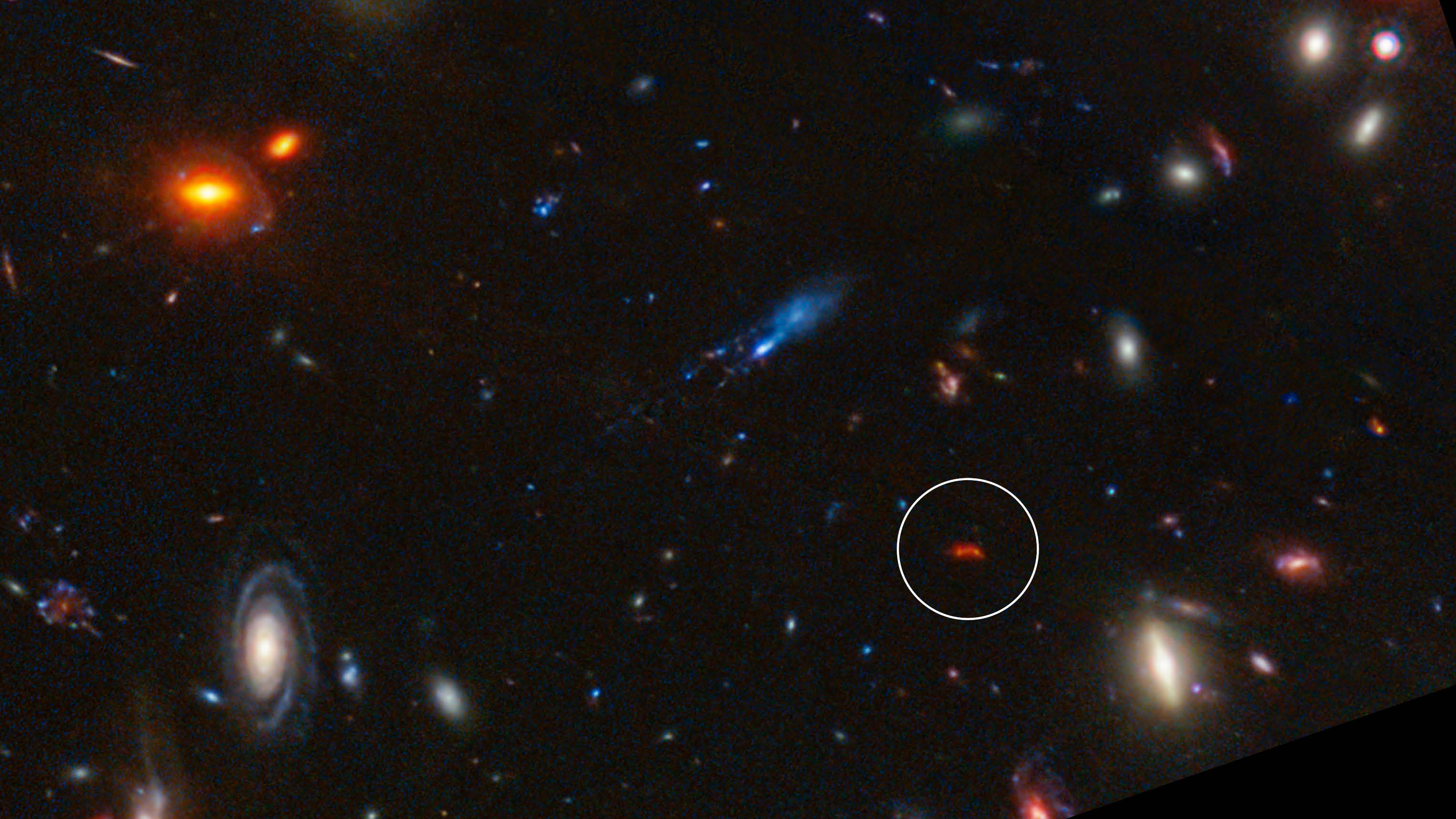

Astronomers discover a superheated star factory in the early universe

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, J. Diego (Instituto de Física de Cantabria, Espagne), J. D’Silva (U. Western Australia), A. Koekemoer (STScI), J. Summers & R. Windhorst (ASU), et H. Yan (U. Missouri)

The first generations of stars formed under conditions very different from those we observe in the nearby universe today. Astronomers study these differences using powerful telescopes capable of detecting galaxies so distant that their light has traveled billions of years to reach us.

Now, an international team of astronomers, including researchers from the Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille. has measured the temperature of one of the most distant known star factories. The galaxy, known as Y1, is so far away that its light has taken over 13 billion years to reach us.

“We’re looking back to a time when the universe was making stars much faster than today. Previous observations revealed the presence of dust in this galaxy, making it the furthest away we've ever directly detected light from glowing dust. That made us suspect that this galaxy might be running a different, superheated kind of star factory. To be sure, we set out to measure its temperature,” says Tom Bakx, the leader of the research team.

The Orion Nebula and the Carina Nebula are examples of such star factories in our own galaxy. They shine brightly in the night sky, powered by their youngest and most massive stars, which illuminate clouds of gas and dust in vivid colors. Like our Sun, stars are forged in huge, dense clouds of gas in space. At wavelengths longer than the human eye can see, these stellar nurseries glow thanks to countless tiny grains of cosmic dust heated by starlight.

"Something truly special"

To probe the galaxy’s temperature, the scientists relied on the superior sensitivity of ALMA—one of the world’s largest telescopes, located in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile. This dry, high-altitude site allowed them to image the galaxy at a wavelength of 0.44 millimeters:

“At wavelengths like this, the galaxy is lit up by billowing clouds of glowing dust grains. When we saw how bright this galaxy shines compared to other wavelengths, we immediately knew we were looking at something truly special,” says Tom Bakx.

Y1 holds the record for the most distant detection of light from cosmic dust.

A "star-making factory"

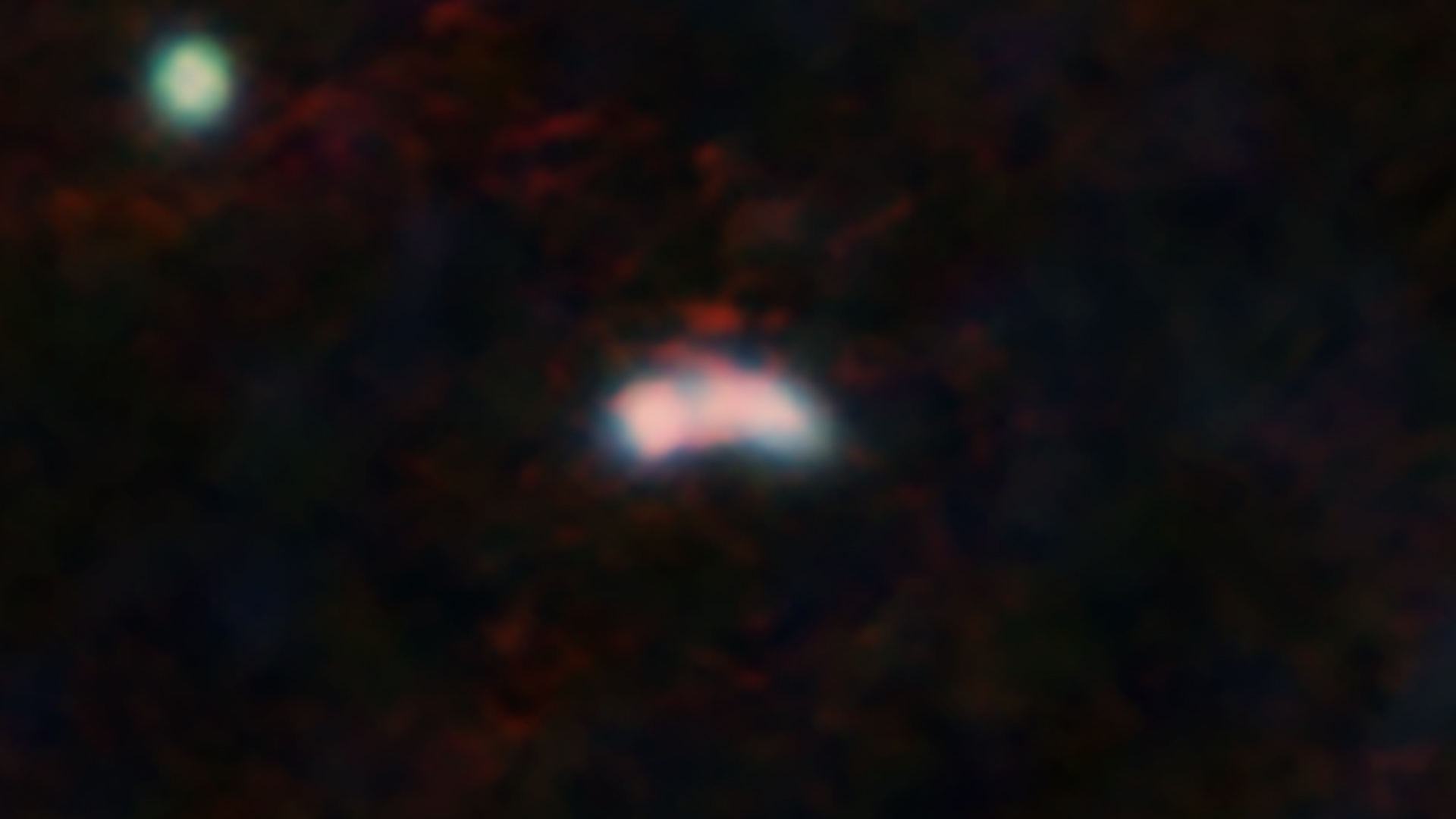

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA (JWST), T. Bakx/ALMA (ESO/NRAO/NAOJ)

The detection revealed the galaxy’s dust glowing at a temperature of 90 Kelvin—around -180°C.

The temperature is certainly chilly compared to household dust on Earth, but it’s much warmer than any other comparable galaxy we’ve seen. This confirmed that it really is an extreme star factory. Even though it’s the first time we’ve seen a galaxy like this, we think that there could be many more out there. Star factories like Y1 could have been common in the early universe,” says team member Yoichi Tamura, astronomer at Nagoya University, Japan.

Y1 is producing stars at an astonishing rate of over 180 solar masses per year, compared to just one solar mass per year in the Milky Way. This pace is unsustainable on cosmological timescales. Brief, hidden bursts of star formation, like those seen in Y1, may have been widespread in the early universe.

"We don't know how common such phases might be in the early universe, so in the future we want to look for more examples of star factories like this. We also plan to use the high-resolution capabilities of ALMA to take a closer look at how this galaxy works,” says Tom Bakx.

On the way to solving another cosmic mystery

Bakx’s team believes Y1 may help explain another puzzle: galaxies in the early universe appear to contain far more dust than their stars could have produced in such a short time. Laura Sommovigo, astrophysicist at the Flatiron Institute and Columbia University, USA, elaborates:

Galaxies in the early universe seem be too young for the amount of dust they contain. That’s strange, because they don’t have enough old stars, around which most dust grains are created. But a small amount of warm dust can be just as bright as large amounts of cool dust, and that’s exactly what we’re seeing in Y1. Even though these galaxies are still young and don’t yet contain much heavy elements or dust, what they do have is both hot and bright,” Laura concludes.

The study, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, opens a new path in the quest to understand our cosmic origins. This research will take a major leap in the 2030s with the opening of the world’s largest optical telescope in Chile—the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT).

Aix-Marseille Université, through the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, is deeply involved in building two ELT instruments: HARMONI and MOSAIC. These advanced cameras will provide unprecedented insights into stardust in distant galaxies.

Latest Highlights:

The University of Tübingen was awarded the 2025 Baden-Württemberg state Teaching Prize

Cutting-edge research at Stockholm University on MOFs, Nobel Prize-Winning Materials

The links between science and beliefs, debated at the amU' Science and Arts Festival 2025